| General learning outcome: | GENERAL WEATHER: | Specific learning outcome: | Vertical air flow and the vertical structure of the atmosphere are important for escalated fire. | Topic: | Key air flows around and within a fire's plume. |

Operational Awareness for Advanced Firefighters & Fire Behaviour Analysts

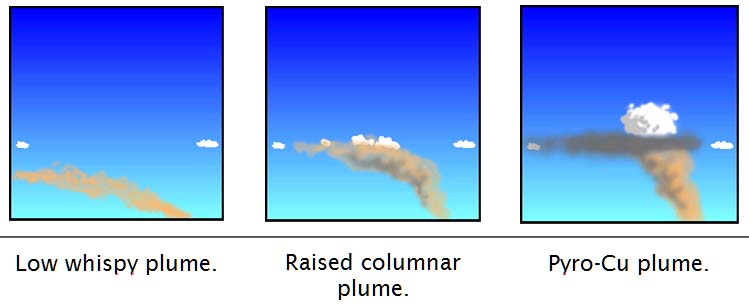

Air flow in and around a plume is complex and variable. A weak fire simply injects smoke into the surrounding air, which moves away with the wind. When a medium fire forms a noticeable plume, it is trying to punch upwards through a horizontal air flow. As this happens some of the air flow is deflected upwards and some is deflected around the plume. A large fire will generate a stronger plume, which will cause greater deflection. In the lee of the plume there will be recurved eddies as the deflected air tries to re-establish equilibrium.

The depth of the flaming zone will be of the same order as the height above ground within which the rising plume resists mixing with the surrounding air, and thus also causes greatest deflection. This reflects the thermal expansion within the rising plume as it seeks to re-establish equilibrium with its surroundings.

For a very large fire these effects start to have the capacity to locally dominate weather.

If the plume resists mixing up to the lifting condensation level, then violent pyro-convection can develop, leading to an extreme fire.

If this happens the plume acts like a solid object in its effects of local surface weather outside the plume. Within the plume localised turbulent circulations dominate.

Strengthening convection may require consideration be given to issuing watchouts or Red Flag Warnings (Conditions conducive to plume-driven fire).

The depth of the flaming zone will be of the same order as the height above ground within which the rising plume resists mixing with the surrounding air, and thus also causes greatest deflection. This reflects the thermal expansion within the rising plume as it seeks to re-establish equilibrium with its surroundings.

For a very large fire these effects start to have the capacity to locally dominate weather.

If the plume resists mixing up to the lifting condensation level, then violent pyro-convection can develop, leading to an extreme fire.

If this happens the plume acts like a solid object in its effects of local surface weather outside the plume. Within the plume localised turbulent circulations dominate.

Strengthening convection may require consideration be given to issuing watchouts or Red Flag Warnings (Conditions conducive to plume-driven fire).

.